Nottingham Skeptics in the Pub begin the year with James Wright talking about Historic Graffiti – The Hidden Story of the Hopes, Fears and Desires of a Nation.

Historic graffiti is a niche study but most counties now have a survey. Graffiti is often thought of as a moronic, transgressive, naughty eyesore – a graffiti artist can tag anywhere. However, sometimes there is a level of artistic skill. There is also a sense of social history, for example, The Castle Ring Melody Men – this could be the only record of this brass band. In a pre-literary society, graffiti is how people so the world, how they understood it and how they coped with their problems. Even doodles have a sense of mindfulness about them.

There are several survey essentials required for looking at historic graffiti – a raking light, DLSR a plan of the building and interpretations:

Craftsmen’s marks – these are not true graffiti, there are marks left by craftsmen/masons where they built things. A mason wouldn’t necessarily keep the same mark but by the 16th century, they became almost a mason’s signature. They were usually relatively straightforward, just 2 to 8 strikes with a chisel. It was also quite common to see stonemasons drawings as they tested out constructions such as arches. These would have been plastered and painted over, The equivalent of a back of a fag packet drawing.

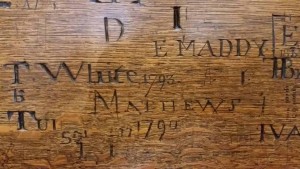

Other types of graffiti – religion holds sway over the nation in the mediaeval period so we see things such as consecration crosses – this is where the local bishop would have touched the walls of the church with sacred oil. Originally, they would’ve been 12 of these in the church but these days it is very unlikely to find all 12. There were also mass dials, these are told bell ringers when to call people in from the fields for mass. Musical notation has been discovered for example in St Albans Cathedral. Crosses often seen in church porches but these are not liturgical rather represent business contracts. Animals are often present and these are the Internet cat of the mediaeval age. Even today, most cathedrals will keep a cat. Graffiti of weaponry is representative of a workman’s labour for example a woodsman’s axe. Heraldry is usually gibberish and it is thought that this may be aspirational. Figures are usually self-portraits while hands and feet or a way of leaving your mark behind, the historical version of “Gary was ‘ere”. There are 100 examples of shoes on the roof of St Mary‘s in Warwick. There are some examples of gallows but these are very rare. When we get to inscriptions, these are more literate graffiti and could be memorials or even merchants leaving their mark – the corporate logos of their day. Graffiti of ships represented people praying that their goods/loved ones would come back safe or sailors wishing the same.

The main type of graffiti is ritual protection marks and around 25 percent all graffiti are these. As well as a fear of evil spirits, demons and witches there was a lot going on at the time that a lot of these apotropaic marks were made

Religious change/tension

Social change (the population doubled between 1530 and 1630)

Enclosure act

Drop in wages

Class tension (in terms of witchcraft, it would be the slightly richer members of society blaming their slightly poorer equivalents)

Witchcraft was made a capital offence in 1542, 1562 and 1604

There was a belief that you could use symbols to drive off evil. This started with the Jewish tradition of the seal of Solomon. In Arabic tradition, this became a six-pointed star while in the west it became a five-pointed star. In the mid-late 14th century, it is mentioned in the poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. It was also believed that a pentangle would pin a demon to the wall and anything that was an endless line became popular, for example, Jacob’s ladder and compass-drawn circles. There were also double V symbols – Marian marks, asking the Virgin Mary for help.

King James said that evil spirits passed around wherever drafts could be found. So, most of these ritual protection marks are found next to doors, windows or chimneys.

People would think that witches were responsible for houses burning down and so they would inoculate their houses with burn marks. These are very prevalent at Queen’s House at the Tower of London, although there are no ritual protection marks in the posh bit of the building, This shows that it wasn’t the rich folk making the marks.

How do you date graffiti? You need to look at it relative to other features such as the reformation whitewash in churches. However, there is some historical graffiti that can be very well dated – the King’s Tower in Knole is riddled with ritual protection marks. One beam has 15 such marks on it and acted as a “force field to protect whoever was in bed from whatever evil spirits came down the chimney. We know that the beam was felled in the winter of 1605 and some of the marks were put on using a carpenter’s tool, so we know that they were added before the beam was put up. The burns on the beam are horizontal, more evidence that the ritual protection marks were put on before the beam put into place. The king at the time was King James I, the witch hunting king and this was just after the gunpowder plot. So, the king has just suffered a stressful event and needs all the protection that he can get, especially since Guy Fawkes et al were considered to be in league with witches and demons at the time.

Skeptics In the Pub returns on the 6th of February at 7:30 at The Canalhouse when Dr Nick Hawes will speak on I, For One, Welcome Our New Robot Overlords. For more information, visit the Nottingham Skeptics’ website http://nottingham.skepticsinthepub.org/

By Gav Squires